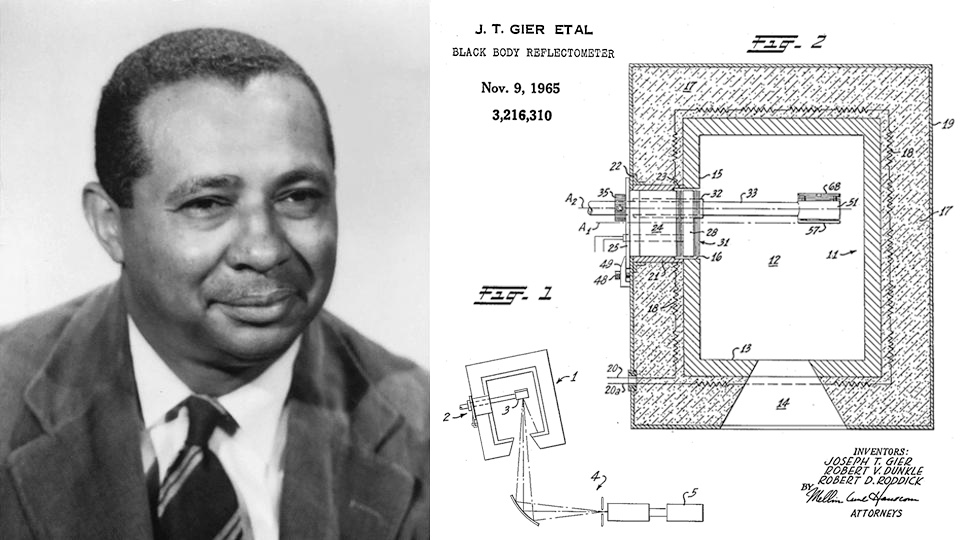

Joseph Thomas Gier

1910-1961

When Joseph Thomas Gier was appointed associate professor of electrical engineering at UC Berkeley in 1952, he became the first tenured Black professor in the entire University of California educational system and the first tenured Black faculty member in a STEM field—and the second in any field—at a top-ranked, predominantly white university in the country (the first was W. Allison Davis, a professor of education at the University of Chicago who earned tenure in 1947).

Wasn’t David Blackwell First?

Although many in the University now celebrate statistician David Blackwell as the first Black ladder-rank professor at Berkeley — he had a dorm named in his honor in August 2018 — Gier was still acknowledged as the first until at least 2003 when he was the subject of a quiz question printed in the General Catalog. It is likely that Blackwell’s oral history, which was also published in 2003, played a role in the confusion. In the Interview History at the beginning of the document, Nadine Wilmot states “When Dr. Blackwell came to UC Berkeley in 1954 after a decade at Howard University in Washington D.C., he became, we think, the first African American ladder rank faculty person systemwide.” However, in the interview itself, Blackwell states that he “wouldn’t be surprised” if Gier had beaten him to it. “He was certainly here when I came. And he had some kind of faculty position, there’s no doubt about that. You have to be careful when you talk about ‘firsts.’”

It would be correct to say that David Blackwell was the first Black full professor at UC Berkeley. Gier became a full professor in 1958.

Early History

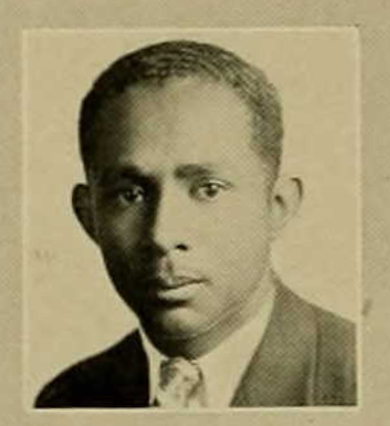

Joseph Gier, 1928

Joe Gier was born in New Orleans on July 2, 1910, the third child of Joseph Thomas Sr., a porter, and Alice Genevieve Fazende, a dressmaker, both from Louisiana. His father died when he was 3 months old, and he and his sisters moved with their mother to Oakland where she took a job as a domestic. Joe grew up in Oakland and attended Roosevelt High School where he appears to have been an extremely well-rounded student. He was on the honor roll, participated in the Christmas pageant, sang with the Hilltop Harmonists (a “double quartette choir”), and was selected for membership in the Alpha Gatta club which provided leadership opportunities for “students who are outstanding in scholarship and citizenship.” He was a member of both the Social Studies and Visual Education groups, the latter of which used “burgeoning educational technologies” like stereographs and slides, to “bring the world to the pupil.” He was the manager of the varsity baseball team, and a letterman in both baseball and basketball. Each high school senior was summed up with a quote in the yearbook, and Gier’s was: “In every thought so good and kind.”

After high school graduation in 1928, Gier worked briefly as a chauffeur and Pullman porter before being accepted to UC Berkeley in 1930. He was elected president of the University of California Alpha Epsilon Chapter of the Alpha Phi Alpha (APA) fraternity in 1932 and lived on Twenty-first Street in Oakland. He earned his Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering (ME) in 1933 and is the earliest known Black student to earn a B.S. in ME from Berkeley.

When Gier graduated from college, he looked for work as an engineer but could only find employment as a designing draftsman for the Alameda High School system and as an “estimator and layout man” for Dempsey Electrical, a private contractor. So, he returned to Berkeley in 1937 as a laboratory assistant and earned his Master’s degree in Engineering in 1940.

Gier married Kathryn Beatrice Catley of Los Angeles in 1939 and they had two sons, Ronald Joseph and Keith Donald.

Gier Dunkle Instruments

Robert Dunkle, 1977

Gier formed a professional partnership with ME Prof. Robert Valentine Dunkle in 1943. He and Dunkle helped define the basic concept of the use of spectral selectivity for the efficient photothermal conversion of solar radiation, and they became world experts in the field of thermal and luminous radiation. Associates considered Gier’s reports on thermal radiation “basic references in the field,” and his “method of measurement of reflectivity and emissivity over the complete range from 1.0 to 23 microns” became recognized as a standard method. It is notable that, although Dunkle was described by former Berkeley Chancellor and ME professor Chang-Lin Tien as “a famous radiation professor,” Gier’s name appears first on their joint inventions. They started a business together to produce their instruments and appear to have been good friends outside of work.

Gier was listed on eight patents filed between 1948 and 1960, six of which listed him as the primary contributor. He contributed in a large share to the developement of the first practical heat flow meter in 1948, to measure heat losses through the walls of engineering structures. Five of his patents were for instruments co-created by Gier and Dunkle including: the Gier Dunkle Total Hemispherical Radiometer, which remained in widespread use for years throughout the world by scientists studying heat balances and heat transfer problems; the Gier Dunkle Infrared Reflectometer, which is still in use today because of its relative speed and accuracy; and the Gier Dunkle Black Body Reflectometer, which became standard equipment in America’s space laboratories where it was used to help select materials which could withstand the searing heat of the sun in outer space. Light and portable, the Black Body Reflectometer was often operated directly on a standing spacecraft for periodic preflight monitoring of coatings’ properties. It was also used to design equipment to harness solar energy on Earth. Gier’s inventions generated revenue for the University of California.

Dunkle, who was a Quaker, left the university and moved to Australia in 1959 because he did not want his research used for military purposes.

[Read more technical descriptions of a few Gier Dunkle Instruments.]

Career at Berkeley

Gier began his career at UC Berkeley in 1939 as a lab technician for the California Highway Patrol Illumination Laboratory, a UC research project that functioned as the agency which tested headlights, taillights, and signaling devices for the State of California Division of Motor Vehicles. He was promoted to Chief Engineer just two years later to fill the seat vacated by his mentor, the Associate Dean of Engineering Llewellyn Michael Kraus Boelter, who left Berkeley to found the College of Engineering at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

Gier was hired as a half-time lecturer in the EE Division in 1946 and was considered by many to be “the best laboratory instructor ever to teach in electrical engineering at Berkeley.” He did not try to “dazzle his students with his erudition,” his colleagues said, “his goal was always imparting understanding.” He had an office in 73 Cory Hall and spent the other half of his appointment as the supervisor of the Thermal Radiation Project for the Office of Naval Research (ONR) in the Institute of Engineering Research (IER). He collaborated on projects with researchers at UCLA and UC Davis, including developing instrumentation to study micro-climatology. He served as a consultant to the US Department of Agriculture “in relation to climatology and environmental studies on animals;” the US Army Engineers’ Cooperative Snow Survey, in which he provided instrumentation to study “energy balances on snow packs as to the effects on snow melting and flood control;” Isoflex Corporation where he evaluated the performance of various types and combinations of low temperature insulation materials for use in refrigerators and vehicles; Coast Counties Gas Association where he designed load studies pertaining to gas distribution systems; and providing thermal instruments to various companies that manufactured glass and plastics, and constructed cooling towers.

He was a very early proponent of solar energy research and energy conservation. He presented a paper at the first-ever international Conference on Solar Energy, held in Tucson, Arizona, in 1955, titled “Selective Spectral Characteristics as an Important Factor in the Efficiency of Solar Collectors.” At the time of his death, his research was dedicated almost exclusively to solar energy.

He was elected to full membership in the scientific honor society, Sigma Xi, in 1949 —a recognition bestowed by invitation only to one who “has shown noteworthy achievement as an original investigator in a field of pure or applied science.” He was also a member of the electrical engineering honor society Eta Kappa Nu (HKN) and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and a full member of both the Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) and the American Society of Refrigerating Engineering (ASRE).

Gier won the APA “Man of the Year” award in 1950 for “achievements in the university” and was put in charge of the Standards Laboratory in Cory Hall, which was used by “most Departments in the University and by scores of outside companies as a ‘West Coast Bureau of Standards.’” Aircraft industries requested numerous measurements from him for various materials used in jet engines and rocket-type missiles. The dual nature of Gier’s research interests, which straddled ME and EE, may have complicated his career trajectory. Nonetheless, he was promoted to Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering with tenure in 1952. He attained the top step of the Associate Professorship in 1955 and remained there until he was promoted to Full Professor in 1958.

Influence

Gier was known for his patience, kindness, and compassion. He had a “friendly and unassuming manner,” was an excellent listener, and took a deep personal interest in his students. Edmund Bussey (’49), thought to be one of the first Black students to earn a B.S. in Electrical Engineering from Berkeley, said that he “looked upon him as a role model,” and one colleague described him as “integrity personified.” The APA gave him a second award in 1956 for “Outstanding Service to the Community and Fraternity” and he was honored by the Los Angeles Urban League in 1960 “in appreciation of an outstanding contribution to the Urban League goal of improving living conditions for minority groups through inter-racial cooperation and action.”

Shortly after his promotion to full professor in 1958, he transferred to UCLA at Boelter’s invitation. His research projects always straddled the fields of ME and EE, but as his interest in solar energy grew, it became clear that the EE department was no longer a good fit for him. He had also been suffering from high blood pressure an hoped the move to southern California might improve his health. He finally succumbed to his illness on June 22, 1961 at age 50, at the height of his career. The Morrin-Gier-Martinelli Heat Transfer Memorial Laboratory at UCLA was partially named in his honor (Gier’s co-honorees, Raymond C. Martinelli and Earl H. Morrin, both studied the thermodynamics of heat transfer and died from leukemia brought on by exposure to Beryllium while doing research on molten metals ). The lab is still used today for “investigating single and two-phase convective heat transfer in energy applications, various aspects of radiation transfer in biological systems, and for material synthesis and characterization.”

Joseph Gier’s legacy lives on. He quietly inspired and influenced the lives of many people who, in turn, influenced the lives of others. By setting a precedent, he made it easier for those who followed him and enriched the academic and scientific landscape for everyone. Lasting change happens slowly and Gier, who believed in the inherent “goodness of man,” led by example.

How did Berkeley lose track of Joseph Gier?

Two primary factors contributing to Gier’s forgotten legacy were probably his untimely death in 1961 at the age of 50, and his transfer from Berkeley to UCLA three years before, during which time he was only able to work intermittently. Most of the students who knew him at Berkeley had left by 1961, and he had not yet had time to fully establish himself at his new campus before his death. Recognition and appreciation of African American contributions only became part of popular American consciousness after the Black Power movement, which had not yet begun when Gier died, and which would not peak for another decade. His youngest students were born one generation too early to bring that awareness with them when they arrived at Berkeley. In 1960, the field of solar energy was still considered “primitive”–photovoltaics were first developed in 1954–and would not gain widespread public attention until the energy crisis of the 1970s. Gier was at least a decade ahead of his time.

Although Gier’s career milestone had been noted in The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, his achievements as a scientist, educator, and African Americon were so singular they appear to have predated a society prepared to recognize them.

Family Legacy

Joseph and Kathryn Gier’s son, Keith, who was only 13 when his father died, graduated from Cal Poly with a BS in Mechanical Engineering in 1971, and attended graduate school at UCLA. Following his father’s footsteps, Keith specialized in the field of heat transfer, and was advised by one of his father’s former students, Prof. Donald K. Edwards. He graduated with an MSME in 1973 and embarked on a career as an aerospace engineer at TRW Defense and Space Systems Group. His manager and early mentor in TRW’s Heat Transfer and Thermodynamics Department was another of his father’s former Berkeley students, Jerry T. Bevans. After his retirement in 2014 from Boeing Space and Communications, Keith has continued working as a contractor at places like the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Lockheed Martin